| ¡International Society

for Education |

| President, 2006- |

Advisory

Board |

|

Lionel McKenzie |

iUniversity of Rochesterj |

| David Pines |

iUniversity of Californiaj |

| Joyce Tsunoda |

iUniversity of Hawaiij |

| James Yorke |

iUniversity of Marylandj |

| Hiroshi Ezawa |

iGakushuin Universityj |

| Hiroshi Ikeda |

iDirector of The Japan Association for Research

on Testing,

Professor Emertus, Rikkyo Universityj |

| Yasuo Morita |

iTohoku Universityj |

| Kazuo Okamoto |

iUniversity of Tokyoj |

| Yoshisuke Ueda |

iFuture University-Hakodatej |

| Kenji Ueno |

iKyoto Universityj |

|

|

Honors

| ¡Japan Mathematical Society,

Publication Prize 2005 |

|

|

Academic Papers

| ¡gBasic Morality and Social Success in Japan”, (with Junichi Hirata, Tadashi Yagi, and Junko Urasaka) |

Journal of Informatics and Data Mining,ol.1, No.1, 2016, Insight Medical Publishing, Delaware, USA.

http://datamining.imedpub.com/basic-morality-and-social-success-in-japan.pdf

|

|

| ¡gImpact of High School Science Studies on Incomes of Japanese University Graduates”, (with Junichi Hirata, Junko Urasaka and Tadashi Yagi) |

| US-China Education Review B, Vol3, no.9, 2013, 651-662. |

|

| ¡gMathematics & Science Education and Income: An Empirical Study in Japan”, (with Junichi Hirata, Junko Urasaka and Tadashi Yagi) |

| Journal of Reviews on Global Economics,

Vol.2, pp.1-8, 2013 |

|

| ¡gAnnual Incomes of University Graduates and their Science Studies during High School Periods”, (with Junichi Hirata, Junko Urasaka and Tadashi Yagi) |

| Recent Advances in Modern Educational Technologies, edited by Hamido Fujita and Jun Sasaki, pp.42-45, WSEAS Press, April 2013. |

|

| ¡gParentsf Educational Background,

Subjects gGood-Ath in Schools affect Income: an Empirical Studyh,

(with Junichi Hirata, Junko Urasaka and Tadashi Yagi) |

| The Japanese Economic

Review,

Vol.57, pp.533-546, 2006 |

|

| ¡gDetection of Thinking in

Human by Magnetoencephalographyh, (with Mitsuo Tonoike and

Yoshikazu Tobinaga) |

| World Congress of Medical

Physics and Biomedical Engineering 2006, IFMBE Proceedings

Vol. 14, pp.2617-2621, 2006 September |

|

| ¡gWorking and Training: A

Nonlinear Dynamic Analysis of Human Capital Developmenth, (with

Tadashi Yagi and Makoto Yano) |

| The Japanese Economic

Review,

Vol.55, No.2, pp.119-140, June 2004 |

|

| ¡gWorking on the brain and

rationality in economic behaviorh, (with Yoshikazu Tobinaga) |

| The Proceeding of the

IJCNN 2003 (The 2003 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks

by the International Neural Network Society and the IEEE Neural

Networks Society), 2604-2608, 2003 |

|

| ¡gStudying Mathematics and

University Education, Labor Income and Career Promotion Empirical

Analysis on the gSurvey on the Effects of Education at Departments

of Economics in Japanese Universities on Career Formationh

(with Junichi Hirata, Junko Urasaka, Tadashi Yagi) |

| Social System Studies, The

Institute of Social System Ritsumeikan University, September

2003, No.7, pp.1-24 |

|

| ¡gThe Role of Mathematics

Education in the Humanities and Social Sciences |

| Mathematics Education in

Japan, Japan Society in Mathematical Education, 38-41, 1998 |

|

Related Newspaper Articles

| ¡The Japan Times, April 11,

2006 |

|

Science crisis in the making |

Last November I

delivered a lecture on complex-system economics at

a world-famous institute

in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I also attended a conference

on science education in the same city, along with a

physicist from Turkey who was visiting there at the

time.

The conference, aimed at improving mathematics and

physics education in the United States, was organized

by David Pines, co-director of the Institute for

Complex Adaptive Matters, and attended by university

and high-school teachers, writers, directors of science

movies, computer engineers and many others. The subject

was how to prepare a teaching program on superconductivity

for junior-and high-school students.

I spoke of my experiences at the author of a math

textbook, gLetfs Study Mathh (not approved by Japanese

censors). The idea behind the book ? providing children

with a text for self-study - received a favorable

response from the audience.

The Turkish physicist Ali Alpar, a professor at

a newly established university in Istanbul, reported

on education there. According to him, Sabanci University

(named after a Turkish businessman) requires humanities

students to study math an physics as well. In the

case of sciences ? physics, chemistry, biology and

geology are organically combined. Generally, the

first three subjects are taught in that order over

a period of two years. Biology is taught last so

that students can learn some of the latest developments

in life science, as in genetic engineering and brain

science.

All this illustrates that the universityfs founding

committee conducted exhaustive discussions to create

an educational institution in the true sense of the

term. It is eary to imagine that students at Sabanci

University are as excellent as those at prestigious

universities of long standing.

By contrast, science education in Japan seems approaching

a crisis. University students in the humanities have

little knowledge of high-school-level sciences. Even

some science students have no experience studying

physics and biology in high school or lack an ability

to make the grade. So universities are left to make

up for these shortcomings.

One reason for all this lies in the way that high-school

science education is provided. According to a survey

by Katsuhiro Arai, professor at Tohoku University,

only 12 percent of students complete physics studies

(category 2), less than the 16 percent of high-school

graduates who enter universitiesf science departments.

Those who similarly study math (category 3) represent

about 20 percent, about the same percentage as those

who enter natural-science departments.

What this means is that many high-school students

not good at math take up science and engineering

courses at universities. With a large number of students

failing to complete studies in physics (category

2) and math (category 3), those who do complete have

a relatively low level of scholastic ability.

The waning interest in math and physics is not a

new problem. The official responses to his has been

to alter the system so that students do not have

to study difficult subjects.

To raise Japanfs technological level it is necessary

not only to spend more time teaching science-related

subjects, but also to increase the number of high-school

students attending science classes. By doing so,

students interested in science should be motivated

to enter science departments. For this to happen,

systemic changes are needed so as to make high-school

science lessons easier to learn.

At present, the science curriculum is divided into

a variety of subjects, such as gbasic sciences,h

ggeneral sciences A,h ggeneral sciences B,h gbiology

Th and gbiology U.h Since the divisions are largely

artificial, study is made unnecessarily difficult.

Science studies in high school will become much

easier if only four subjects ? biology, chemistry,

physics and geology ? are taught. In face, that was

the case in the 1960s, when high-school students

learned most of the basics about these subjects.

At Sabanci University, physics, chemistry and biology

as well as geology are taught in an integrated manner,

incorporating their basic elements. Biology has a

fast-developing branch that requires knowledge of

physics an chemistry. By the same token, knowledge

of biology and geology is essential to an understanding

of global environmental problems. Basic to this are

chemistry and physics.

Physics should be studied first because it is a

more basic and logical branch of science. That should

make it easier to understand more applied subjects.

That is also an efficient way to study a number of

science subjects. At least high schools preparing

for university entrance exams, if not all high schools,

should provide such guidance.

In the past, as many as 80 percent of high-school

students studied gphysics T.h Now, however less than

30 percent complete the course. This is hardly the

way to build a technology-oriented nation. |

(By KAZUO NISHIMURA)

|

|

|

| ¡Japan Times, July 7, 2002 |

|

|

Professor laments

decline of academic standards across board

|

Academic Kazuo Nishimura is convinced

that Japan will face devastating consequences if the

government continues to dilute the academic curricula

of elementary and junior high school students.

Nishimura, a professor at Kyoto Universityfs Institute

of Economic Research, said in a recent interview with

The Japan Times that the level of understanding required

under the latest curricula, introduced in April, is 30

percent lower than under the previous system. This will

only lead to a deterioration in the already-low intellectual

capabilities of Japanese students, he warned.

A specialist in the field of complex economics, Nishimura

cited the dangers stemming from falling academic standards

among university students in his 1999 book gBunsu ga

dekinai daigakuseih (gUniversity Students Who Cannot

Solve Factions).h

He claimed, however, that the situation has only worsened

since then. gThis can be attributed to the policy of

eeasing educationf put forward by the Education, Culture,

Sports, Science and Technology Ministry and to the introduction

of multiple choice exams for university entrance,h he

said.

Beginning in 1980, the ministry has been reducing class

hours and study courses at elementary and secondary schools.

The multiple choice exam format was first introduced

at national universities in 1979. Since 1990, private

universities have also been allowed to use this exam

format, while students across the board have been allowed

to choose the subjects featured in their multiple choice

tests.

Nishimura noticed a decline in studentsf academic performance

around 1985.Moreover, the results of math tests conducted

by the professor at several universities in 1998 showed

that a considerable number of freshmen, particularly

those who did not take math as an entrance exam subject,

could not solve simple problems.

He sensed an even sharper drop in 1999, when freshmen

who were taught under the second set of revised curricula

entered university.

|

(By KENZO MORIGUCHI, Staff writer)

|

|

|

| ¡The Nikkei Weekly, March

25, 2002 |

|

|

| School

daze |

Japanfs

education system has been under fire for years,

but with new, more lax curriculum guidelines, critics

worry students will fall behind their counterparts

overseas

|

Tatsuyqa deguchi,

a math teacher at a high school in Wakayama, southwest

of Osaka, has watched with growing dismay as his

studentsf math ability has plummeted. Especially

in the past five to six years, Deguchifs dismay has

turned to alarm as the problem has gotten progressively

worse.

gRecently we gave our 10th grade students a math test

meant for first- to third-graders, and two-thirds of

the 240 students couldnft multiply two-digit numbers.

Only half could calculate the area of a triangle using

the length of the base and the height,g Deguchi said.

¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥

However, the situation will probably get worse because

of revised government curriculum guidelines to be introduced

this April. The new guidelines continue the more lax

education policy, which started in 1977 as a reaction

to the cramming-centered system that was believed to

be stifling studentsf creativity, so many fundamental

skills were removed from textbooks, while 70 study hours,

nearly 7% of the annual total, were slashed from public

elementary and junior high school curricula.

¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥

Ongoing revision

The government has revised its curriculum guidelines

for the compulsory first through ninth grades, every

10 years or so since 1958. Until the mid-1970s, the guidelines

were adjusted to enrich the content of education. But

in the late 1970s, there was growing public consensus

that too much emphasis on passing exams was harmful to

childrenfs development and causing stress as a result

of the brutal competition for university entrance examinations.

Therefore, so-called gpressure-freeh education gained

favor and the government started simplifying the content

of textbooks to allow students the freedom to develop

their individuality.

gThe most important thing is to encourage students to

think for themselves, not to cram facts into their heads

just to get better scores. To motivate them to study,

we consider a fertile sensibility and a healthy body

to be crucial,h said Yusuru Imasato, head of curriculum

planning at the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports,

Science and Technology.

Imasato explained that the major cuts in the textbooks

will help students who cannot keep up with the classes,

while enabling teachers to have closer contact with students.

In addition, under the new guidelines, despite a major

slashing of study hours devoted to existing subjects,

some 100 hours will be allocated to gcomprehensive learningh

aimed at enabling schoolchildren to have hands-on learning

about nature being apart from textbooks.

¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥

Even Japanfs top university professors are strongly criticizing

the government curriculum guidelines as gBureaucratic

and harmful.h

gThe pressure-free education system is nothing more than

bureaucratic talk. The contradictory educational policy

has harmed many schoolchildrenfs future and possibility,

by taking away their opportunities and eagerness to learn,h

said Hirofumi Uzawa, professor emeritus in economics

at the University of Tokyo. Uzawa believes the recent

drop in the math ability of schoolchildren reflects an

educational policy that results in math textbooks that

are gless attractiveh for many students by merely showing

formulas.

Similarly, Kazuo Nishimura, professor of economics at

Kyoto University, sighs over the severe deterioration

of math ability among economic majors, especially those

who did not take math classes at high school because

most top-class private universities do not include mathematics

in their entrance examinations.

gAmong those economic majors at top university who didnft

take math courses at high school and didnft take a math

test in the entrance examinations, more than 20% canft

do elementary school level arithmetic, such as addition

and subtraction of fractions,h Nishimura said.

The professor pointed out another problem \ Japanese

schoolchildren have the fewest study hours for math among

the Group of Seven major industrialized countries. For

instance, Japanese seventh graders take a total of 99

hours of math classes annually, while U.S. students in

the same grade take 146 hours, French students 129 and

U.K. students 117.

gIn terms of the volume of content and the difficulty

of questions, math textbook for Japanese schoolchildren

are two to three years behind the ones used in China,

South Korea and Singapore. As long as the government

keeps the current pressure-free education system, Japan

will inevitably lack the human resources to maintain

global competitiveness,h Nishimura said. He stressed

the importance of basic ability gained from repeated

practice, such as arithmetic and writing, not only for

mathematics but for other subjects too.

By the same token, many parents send their children to

private schools with unique educational curricula to

improve their academic ability, rather than to public

schools that have to follow guidelines provided by the

government. ¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥¥

|

(By MINA HASEGAWA, Staff writer)

|

|

|

| ¡The Daily Yomiuri, January

27, 2000 |

|

|

Survey: Humanities

Students poor at math

|

About 25 percent of first year

students enrolled in humanities courses at leading

national and public universities are unable to solve

basic mathematical problems involving the four rules

of arithmetic and decimal fractions, according to the

findings of a survey.

These findings demonstrate that poor mathematical ability

among university students is not limited the economics

departments of private universities, which do not require

candidates to take math for their entrance examinations.

Rather, it is becoming common in all departments.

The survey was conducted in April by Kazuo Nishimura,

an economic of complexity professor at Kyoto University,

and Prof. Nobuyuki Tose, who teaches mathematics at Keio

University. It covered the humanities divisions of 11

national and public universities, most of which have

their origins as Imperial universities.

About 1,300 first year university students were asked

to solve 22 middle-to high-school-level math problems.

They were chosen from basic-level questions in the daiken

test\a scholastic aptitude test that enables students

that pass to sit university entrance examinations without

graduating from high school.

To even out and randomize the test subjects, the survey

was conducted during classes that are compulsory for

all students.

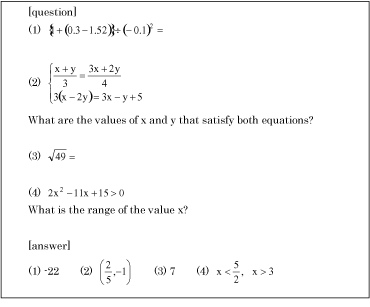

At the top national university in eastern Japan, 73 percent

of students solved Question 1 (see chart), a first-year-middle-school-level

problem that involves all four fundamental rules of arithmetic

and decimal fractions. However, the percentage of correct

answers dropped to 33 percent among students who had

not taken math in entrance exams.

Question 2, a second-year-middle-school problem that

involved a linear equation, was answered correctly by

86 percent of students. Question 3, a third-year-middle-school

problem that involves square roots, was solved by 83

percent.

However, the students fared considerably worse on high-school-level

problems.

While, 87 percent of the students overall solved Question

4, which involved a quadratic inequality, the ratio dropped

to 22 percent among students who had not taken math in

the entrance exam.

Results at this university proved that there is a large

gap in scores between students who did not take math

in the entrance exam and the student body overall. The

former group scored only 32 percent on average, while

the average for students as a whole was 83 percent.

The same trend has been observed in other national and

public universities.

At western Japanfs premier university, 75 percent of

students solved Question 1.

Average scores among the 11 schools ranged between 60

to 92 percent at that university.

Nishimura and Tose conducted a similar survey on economic

students at private universities in 1998, and concluded

that students who had not taken math in entrance exams

were generally not strong in the subject.

gThe survey results show that poor mathematical ability

is also a problem at national and public universities.

Some say that math is not necessary for students in humanities

divisions, but I doubt how much logical thinking students

can do if they do not a have basic grounding in arithmetic.

I think that the three foundation subject: math, Japanese

and English, should be made compulsory components of

entrance exams.h Nishimura said.

|

|

|

|

| ¡The Daily Yomiuri, November

2, 1998 |

|

|

| University

students failing in basic mathematics |

1

out of 5 pupils unable to solve simple problems

|

One out of five

students at private universities cannot solve questions

on mathematics at the primary school level despite

being enrolled in courses that require some knowledge

of the subject, a survey released Saturday revealed.

The survey results underscored a report issued last month

by the University Council, an advisory body to the education

minister, that called for entrance examinations to test

potential university students on high school subjects

relevant to their further education.

The survey covered about 5,000 first-and second-year

students, mostly at economics department, of eight state-run

universities and 11 private institutions. It was conducted

in April by Kyoto University Prof. Kazuo Nishimura.

The students, who encounter math in lectures every day,

were asked to solve 25 basic questions on areas of the

subject that they had studied before high school.

Of students at one private universityfs economic department,

82 percent of the respondents were able to answer one

primary school-level question correctly. The entrance

exam for the department does not include a mathematics

test.

The students at the second private university did only

slightly better, registering a pass rate of 86 percent.

The figure fell for questions at the middle school level,

with the two universities registering success rates of

56 percent and 77 percent, respectively.

When tested on quadratic equations taught in the third

year of middle school, only 13 percent of students at

the former university and 28 percent at the latter could

give the correct answer.

gStudents who want to study economics at the university

level should at least be tested in mathematics in entrance

exams,h Nishimura said.

|

|

|

|

|